23rd Sunday after Pentecost – Vicar Stoppenhagen

23rd Sunday after Pentecost

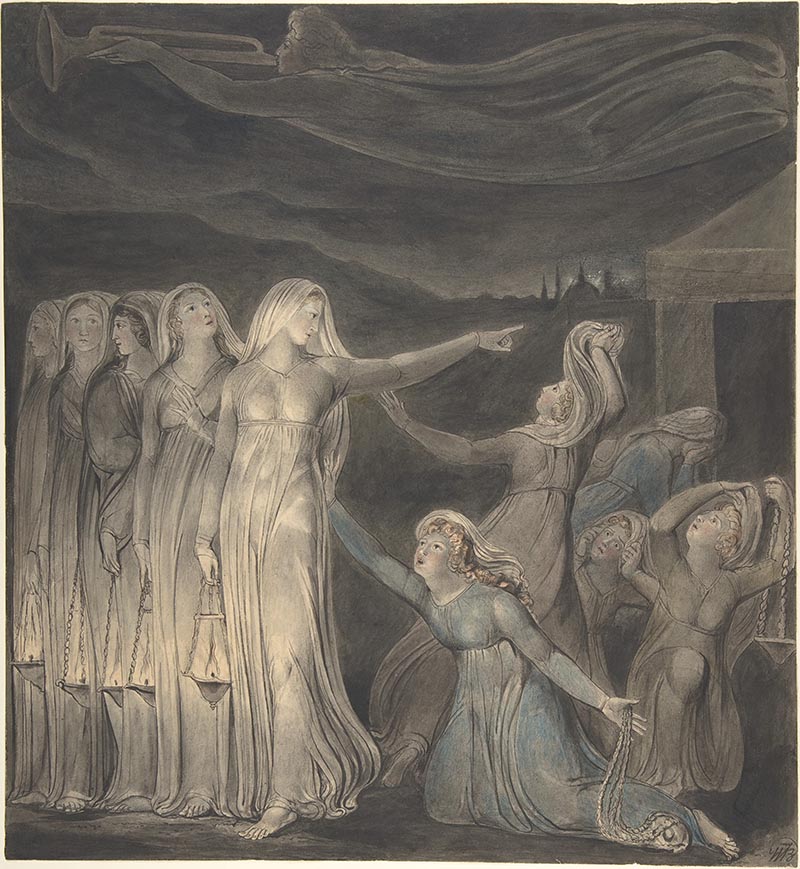

Text: Matthew 25:1-13

Our Savior Lutheran Church, Raleigh

November 8, 2020

In the name of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who is coming into the world. Amen.

These last few Sundays of the church year always make me a little uncomfortable, because all of a sudden, Jesus gets mean. Last week he was blessing the poor and the mourning and the peacemakers, but this week he’s slamming the door in the faces of the foolish. If you’re not very bright and don’t know how to plan ahead, consider your invitation revoked. And don’t expect your friends to help you out. They’re going to look at you stone-faced and send you off to buy your own oil. Parables like these are unpleasant, because it seems like Jesus only loves some of the little children of the world.

Our Jesus is supposed to know everyone and love everyone and include everyone in his kingdom. “Come on in!” we expect the bridegroom to say. “All are welcome in this place!” But instead we get those devastating words, “Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.” “What do you mean?” the virgins say. “You remember us! It’s me, Jana! Remember? Nazareth High, Class of A.D. 22?” “Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.” “But you invited us to the wedding…we were here earlier but you were late, and we had to run and get some—” “I said, I don’t know you.”

Why does Jesus suddenly forget who he’s invited into the kingdom? Maybe he honestly doesn’t know them. “Class of 22, you say? I graduated in 20. I don’t think we’ve ever crossed paths.” But Jesus is all-knowing, so he surely knows who these virgins are. He could just be faking it to teach them a lesson. “You think you can come to my party without enough oil? You want to show up without your wedding garment? No such luck. You’re out.”

But the bridegroom isn’t being selective or forgetful or vindictive. He simply doesn’t recognize the foolish virgins. From the get-go, they were supposed to be included in the wedding feast, but something about them changed. Something was missing that made the bridegroom unable to see who they were. The one thing that changed was, quite simply, that their lamps went out.

The virgins’ lamps weren’t just so they could see the pathway to the wedding hall. Anyone could have made it there in the clear, moonlit night. The lamps were so that other people could see them. The light illumined their faces, so they could be identified by those passing on the road. That’s why the lamps were so important—not only so that the virgins could see the way, but so that they could be recognized by others as people who belonged in the bridal party. Without their lamps, they were simply unrecognizable shadows. Without the light, they had no identity.

So when the cry comes that the bridegroom is coming, the foolish virgins take off into the night, because their lamps are going out. They must scrounge up whatever oil they can to keep their lamps lit so that the bridegroom will be able to recognize them. But as far as we know from the text, they don’t have any luck. No dealer, except maybe the shady kind, is going to be available at midnight. So they grope their way through the darkness back to the wedding hall. They knock, but when the bridegroom peeks out, it’s too dark for him to see. “I can’t see who you are. I don’t remember your voices. Truly, I do not know you.” The bridegroom knows who’s on the guest list. But without their lamps, the virgins were unrecognizable and left in the darkness.

In a parable like this, it’s easy to point the finger at someone else. After all, the foolish virgins were invited to the wedding feast, so they should have been welcomed in no matter what. Who cares if they were unprepared and ultimately showed up late? Better late than never! Besides, the bridegroom himself was late to his own party, so who’s he to condemn? Those wise virgins should have been a little nicer, too. They could have made the sacrifice and shared a little oil with their friends. Why were they so selfish? Or they could have let at least let the bridegroom know that the foolish virgins would be there eventually, after they found some more oil.

This shows us one of the tough things about believing in Jesus. We don’t get to set the terms for our faith. Once invited, always invited isn’t how it works. You can’t just show up whenever you feel like it. You can’t blame other people for your own lack of faith. Jesus isn’t going to show up when you expect him to. Other people can’t believe for you. Faith on our own terms isn’t faith at all. It’s just another form of sinful self-centeredness.

Faith isn’t about what you know or what you feel, either. Just because you have a vast biblical knowledge or deep Lutheran roots or that feeling of joy down in your heart, doesn’t make you a believer. It’s not you knowing Jesus. What makes you a believer is Jesus saying, “I know you.” Faith is on his terms. What makes you Christian is Jesus recognizing you and knowing you as an heir of his kingdom. If we try to establish faith on our terms, it simply becomes more uncertain, and we’re even more likely to be left out in the dark.

But if we recognize that our faith is on Jesus’ terms, we can be confident that he won’t falter on his promises. He is the Light in our lamps and we trust that he will have more than enough oil, so that when he comes he will recognize us as his own. But that doesn’t mean we should be careless. It’s our duty as members of his wedding party to make sure our lamps stay lit and that we’re awake at his coming. The flame of faith can be quickly extinguished, so we must feed it with the oil of his gifts—the gifts of the Sacraments, prayer, and his Word. These gifts don’t just feed our own flame of faith, but they make you that much more visible to him. Receiving God’s gifts imprints you on his heart, so that he doesn’t forget you.

Pastor shared with me this week something he learned from the sainted Norman Nagel when he was at the St. Louis Seminary. When Jesus institutes the Lord’s Supper (in the version from Luke), he doesn’t say, “Do this in remembrance of me.” He says, literally, “Do this into my remembrance.” Do this, not so that you will remember me, but that I will remember you. Every time you partake of the Lord’s Supper, you are pressed deeper into God’s memory, deeper into his heart.

The same thing happens when you pray. How do we sometimes introduce the Lord’s Prayer? “Lord remember us in your kingdom, and teach us to pray…Our Father…” Every time you pray, you’re reminding your heavenly Father of your status as his child. Every time you pray, every time you share with God your confessions, your laments, and your joys, you remind him of your dependance on him. You etch yourself into his memory so that he can’t forget his promises to you.

In the end, maybe Jesus isn’t as mean as we think he is. Like a friend who notices we’re starting to get lazy on the job, he’s pushing us into a deeper attentiveness. He’s driving us out of our comfortable Christianity and into a bolder confession of him. He’s reminding us that we don’t set the terms for our faith in him. Finally, he’s encouraging us to keep loading up on fuel, so that our lamps will burn ever brighter into that dark night. And when he arrives, he will see you and say, “I know you! Come on in. All has been prepared. Come to the wedding feast.”

In the name of Jesus. Amen.